Transform Business. Gain Focus. Part 2 - Quadrant Analysis

While most investors are taking a disciplined approach, we have seen instances over the past few months of deals that simply don’t make sense. Anthony Bahr presents three examples of deals gone wrong...and what you can do to mitigate before it's too late.

It was the least active year in M&A transactions in a decade. It seems the industry hoarded their dry powder and awaited EBITDA-C to return to EBITDA. I marvel at how quickly we catapulted into a deal-making renaissance and at how much pressure institutional investors are under to deploy capital. We’ve worked on ~40 deals in the past six months; last year we worked on a total of 30.

While most investors are taking a disciplined approach, we have seen instances over the past few months of deals that simply don’t make sense.

As investors head into Q4, historically the most active quarter for deal-making, here are three examples of deals that have gone bad and how due diligence and value creation strategies can be designed to mitigate these risk factors.

A financial buyer was considering a platform investment in a niche professional services vertical. The target had 213 customers and cited a Net Promoter Score of +82 as evidence that the revenue base was secure.

However, revenue was highly concentrated and three of the target’s 213 customers generated 50% of the revenue. While the target’s NPS was +82 in total (a great score) the NPS for its top three accounts was -100 (as bad as it gets). When we spoke with decision-makers at these top three accounts, all of them explicitly stated that spend with the company would decrease in the next twelve months.

Our client passed on the deal, but another investor closed six months later. It’s like cheating off the kid in class that always gets an F; what did they think was going to happen? Within a year of closing, two of the three top accounts had pulled all of their spend and the third had significantly lowered its spend.

Mitigant: NPS is an important input when underwriting the stability of the customer base, but the textbook definition (percent of promoters minus the percent of detractors) can be extremely misleading when there is customer concentration. Use a revenue weighted NPS so that each customer’s input is proportionate to their share of revenue.

A private equity investor closed on a manufacturing company in Q3 2020 and the short-term value creation strategy was rooted in the elimination of “Quad 4” – unprofitable customers that purchase unprofitable products.

In the case of this company, Quad 4 consisted of 1,592 customers and 820 products. In other words, this segment of the business included 75% of the company’s customers and 71% of its products but it only generated 8% of total revenue. While Quad 4 generated $6.8M in gross margin, it took roughly $14M in operating expenses to service this segment of the business resulting in a $7.2M operating income loss.

Post-close, the Board mandated a Customer Line Simplification and Product Line Simplification workstream be competed in the first three months post-close. Conceptually the CEO understood how simplification would drastically improve profitability. In reality, the CEO – who was also the founder of the company and owned many customer relationships – could not drive the change that was needed. The CEO let emotion-based decision-making override data-based decision-making.

Today, the company is falling significantly short of modeled returns because the company has not eliminated Quad 4 and its profit-eroding complexity.

Mitigant: Use operating partners and outside advisors to be the voice of reason and drive the difficult, emotionally-charged change that many portfolio companies need to make.

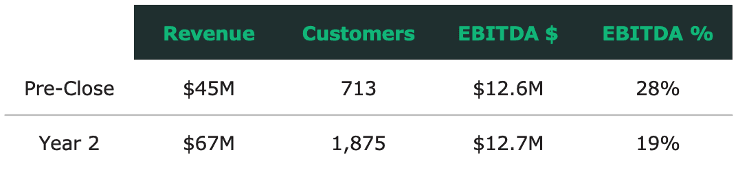

A distribution company was acquired by a family office in 2018 at a 6.5X EBITDA multiple. Pre-close, the company generated $45M in revenue with $12.6M EBITDA margin (28%).

Given healthy margins, the post-close mandate was rightfully to accelerate topline growth, and the company succeeded in doing so. Between 2018 and 2020, the company added $22M in revenue (a 49% increase). Unfortunately, the company grew by adding hundreds of small, low-volume, non-strategic customers that tended to buy custom rather than standard products resulting in gross margin compression. To manage the additional complexity, the company had to significantly increase its SG&A costs.

While revenue was now $67M, the company’s EBITDA margins had shrunk from 28% to 19% or $12.7M. Essentially, the company was making the same amount of money for doing double the work. If the company was sold today at the same multiple, the transaction would generate a return of less than $1M in two years.

Mitigant: When companies grow, ensure they grow with whales, not minnows. Use a target selling strategy to grow with one extraordinary partner rather than ten ordinary accounts.

The common thread that weaves these examples together is the fact that complexity is the most prominent obstacle to successful M&A deals. Complexity not only erodes profitability, but it bogs down decision-making and distracts management teams from focusing on what matters most: profitable market share growth.

----

Anthony Bahr is Managing Director of our Customer Due Diligence practice. When he's not advising private equity clients on customer risk, he guest lectures on consumer behavior and research methodologies at Cornell University, Loyola University Chicago, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Connect With Anthony

Connect With Anthony

Customer Due Diligence Impact

$21M

Avg Savings Per Deal

Transform Business. Gain Focus. Part 2 - Quadrant Analysis

Transform Business. Gain Focus. Part 2 - Quadrant Analysis

How a Private Equity Firm Saved an Easy $6M

How a Private Equity Firm Saved an Easy $6M

A Coming PE Surge: A Collaboration with PitchBook

A Coming PE Surge: A Collaboration with PitchBook

Contact us to see how we can help your business today.

Never miss a beat. Get our latest insights in your inbox.